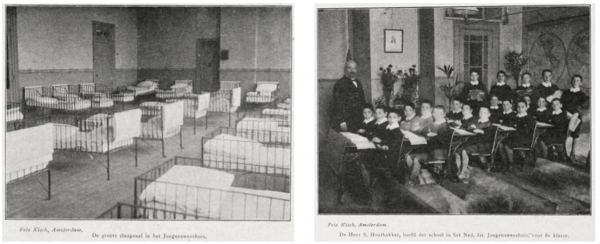

Within the Portuguese-Israelite community in Amsterdam, the first organisation to look after orphans was founded in 1647, under the name Abi Jethomim. This organisation was for boys only. Following this, an orphanage was established in 1738, which was called Megádle Jethomim (‘upbringing of orphans’). Initially, this place looked after education, health care and assistance in seeking jobs. However, during the eighteenth and nineteenth century the care for orphans was expanded due to higher demands.

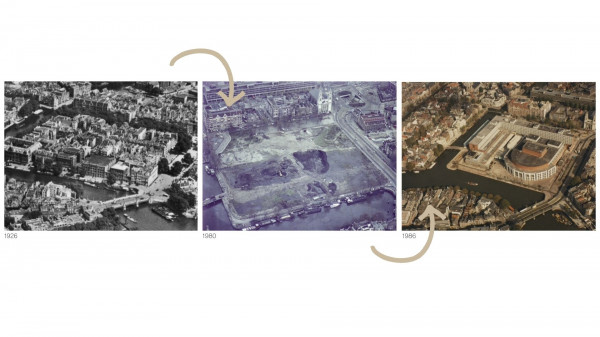

Within the Portuguese-Israelite community in Amsterdam, the first organisation to look after orphans was founded in 1647, under the name Abi Jethomim. This organisation was for boys only. Following this, an orphanage was established in 1738, which was called Megádle Jethomim (‘upbringing of orphans’). Initially, this place looked after education, health care and assistance in seeking jobs. However, during the eighteenth and nineteenth century the care for orphans was expanded due to higher demands.  What is now known as Waterlooplein used to be a neighbourhood called Vlooienburg, the heart of Jewish life in Amsterdam. Around 1600, the Vlooienburg was created near the Amstel, consisting of only three streets: Lange Houtstraat, Korte Houtstraat, and Zwanenburgerstraat. As described by the municipality of Amsterdam, there were a few thousands of people living there, generally speaking in poor conditions. In 1882, the neighbourhood was transformed into Waterlooplein. Because of the high concentration of Jewish people living there, it eventually became an easy target of Nazi troops in the 1940s. People were deported in large groups, soon leaving the area empty. Whereas first almost 80,000 Jewish people were living there, after the War this number was reduced to a scarce 10,000. Eventually, the Jewish neighbourhood was remodelled by the municipality, which resulted in the demolishment of most of the original houses and buildings- including the Megádle Jethomim orphanage.

What is now known as Waterlooplein used to be a neighbourhood called Vlooienburg, the heart of Jewish life in Amsterdam. Around 1600, the Vlooienburg was created near the Amstel, consisting of only three streets: Lange Houtstraat, Korte Houtstraat, and Zwanenburgerstraat. As described by the municipality of Amsterdam, there were a few thousands of people living there, generally speaking in poor conditions. In 1882, the neighbourhood was transformed into Waterlooplein. Because of the high concentration of Jewish people living there, it eventually became an easy target of Nazi troops in the 1940s. People were deported in large groups, soon leaving the area empty. Whereas first almost 80,000 Jewish people were living there, after the War this number was reduced to a scarce 10,000. Eventually, the Jewish neighbourhood was remodelled by the municipality, which resulted in the demolishment of most of the original houses and buildings- including the Megádle Jethomim orphanage.

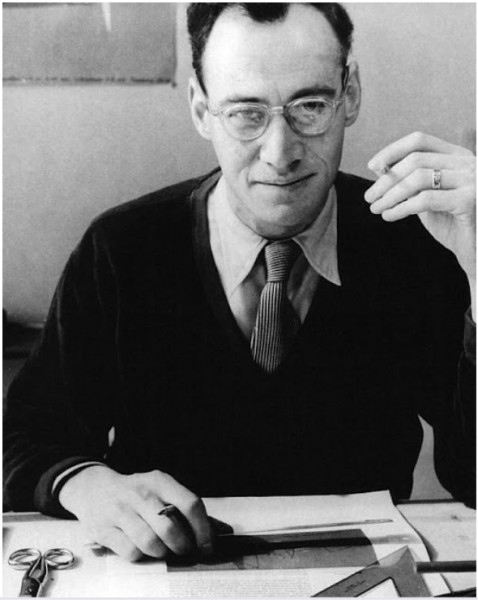

Otto Treumann was a graphic designer born 1919 in Fürth, Germany. Due to him being from a liberal Jewish family, he had to flee the country in 1935 from the Nazis and landed in Amsterdam, where he started to study graphic design Amsterdamse Grafische School. While in hiding, he spent mush time creating illegal printings of fraudulent identity cards and coupons. Treumann is mostly known for his work as a graphic designer, with grand projects together with Bond van Nederlandse Architecten, Rayon Revue, memorial stamps for the Dutch postal service and much more. He is also known for his contribution of Holocaust memorials, and was specifically asked to design the memorial of Megádle Jethomim by Joods Maatchapplijk Werk, who commissioned the memorial in mid 1980s. Treumann passed away in 2001, and mush of his work and private collections can now be found at the Allard Pierson archive.

Otto Treumann was a graphic designer born 1919 in Fürth, Germany. Due to him being from a liberal Jewish family, he had to flee the country in 1935 from the Nazis and landed in Amsterdam, where he started to study graphic design Amsterdamse Grafische School. While in hiding, he spent mush time creating illegal printings of fraudulent identity cards and coupons. Treumann is mostly known for his work as a graphic designer, with grand projects together with Bond van Nederlandse Architecten, Rayon Revue, memorial stamps for the Dutch postal service and much more. He is also known for his contribution of Holocaust memorials, and was specifically asked to design the memorial of Megádle Jethomim by Joods Maatchapplijk Werk, who commissioned the memorial in mid 1980s. Treumann passed away in 2001, and mush of his work and private collections can now be found at the Allard Pierson archive.

We define the memorial of Megádle Jethomim to be a ground-based memorial, meaning that the memorial is not only on the ground, but displayed on ground level, making it intertwined with the pavement that you may walk upon everyday. Ground-based memorials are not uncommonly used, and can be found around the city of Amsterdam, from Dam Square to the Livestock market, and are a way to memorate the people that walked on that same ground years ago. However, when visiting the memorial of Megádle Jethomim, one quickly sees how it being part of the pavement makes it difficult for people to notice the memorial at all.

We define the memorial of Megádle Jethomim to be a ground-based memorial, meaning that the memorial is not only on the ground, but displayed on ground level, making it intertwined with the pavement that you may walk upon everyday. Ground-based memorials are not uncommonly used, and can be found around the city of Amsterdam, from Dam Square to the Livestock market, and are a way to memorate the people that walked on that same ground years ago. However, when visiting the memorial of Megádle Jethomim, one quickly sees how it being part of the pavement makes it difficult for people to notice the memorial at all.

We hope that creating the opportunity of placing pebbles at the memorial, according to Jewish tradition, will increase interaction between the place and the Jewish community of Amsterdam. Through that interaction, we believe more people will start noticing the memorial is there.

We hope that creating the opportunity of placing pebbles at the memorial, according to Jewish tradition, will increase interaction between the place and the Jewish community of Amsterdam. Through that interaction, we believe more people will start noticing the memorial is there.

The second prototype concerns an information booklet, which should contain a cohesive source of information on the memorial. As part of the last Design Thinking Phase – Testing – we held conversations with others to explore what the content of such a booklet should be.

The second prototype concerns an information booklet, which should contain a cohesive source of information on the memorial. As part of the last Design Thinking Phase – Testing – we held conversations with others to explore what the content of such a booklet should be.